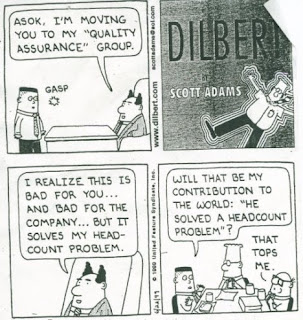

As paradoxical as the title seems there is a profound truth in the statement "Less is More". When the economy is bullish no one talks about "head count issues", they just keep adding resources at will. People come up with innovative justifications why more resources are needed for a project, and there is little resistance from the management. Many support functions sprout, new centre of excellence teams that has no clear business impacts start to grow, many cross-functional teams are setup and so on and so forth.In addition many projects without complete business justification get approved. The success rate of the new products launched is not that great, but the business managers are not held accountable as the overall growth of the company isn't that bad. Over a period of time these additional resources increase the waist-line of the organisation. On top of it, terminating an employee when business is hunky-dory is a tough bullet to bite for most managers. So, on an average across the company, you find more resources than is required for the business.

As paradoxical as the title seems there is a profound truth in the statement "Less is More". When the economy is bullish no one talks about "head count issues", they just keep adding resources at will. People come up with innovative justifications why more resources are needed for a project, and there is little resistance from the management. Many support functions sprout, new centre of excellence teams that has no clear business impacts start to grow, many cross-functional teams are setup and so on and so forth.In addition many projects without complete business justification get approved. The success rate of the new products launched is not that great, but the business managers are not held accountable as the overall growth of the company isn't that bad. Over a period of time these additional resources increase the waist-line of the organisation. On top of it, terminating an employee when business is hunky-dory is a tough bullet to bite for most managers. So, on an average across the company, you find more resources than is required for the business.When the business is bearish or during tough times like the present, the organisation is forced to shed the flab. The first steps are to reduce the contract headcounts-easiest of the decisions, reduce the headcount from support organisation, terminate the bottom 10% performers, question the premise of the centre of excellence teams and cross functional teams. Even after all these actions, if you, as a manager, cannot meet the set goals of head count reduction in your group, you start to look at the product portfolio and see which projects can be cancelled (to start with, you would not be in this position if all the projects approved had concrete business justifications). This action causes you to lose good performers. The head count reduction actions taken across the organisation lowers the morale of employees who still have a job as there is the uncertainity of when the axe is going to fall on them.

When you look back, you realise that the massive layoffs, during these tough times, is the result of the organisations not being resource-prudent to begin with, during the bullish time. Interestingly even with the reduced work force, the number of projects that an organisation does is not reduced. There could be cases of some employees working longer hours but definitely not for all the employees. So how come with less people more work gets done? Is "Less is More" not really a paradox?

To support this point, I will share with you " The case of panicky mice" - An experiment with panicky mice that confirms the reality that less is more and therefore better, not the other way around. The "New Scientist" reported the results of an experiment by a University of Phillipines professor of physics, on how panicked mice escape from an enclosed area. He developed his model based on some mice escaping, from a contained water pool onto a dry platform through doors of various widths and separations.The experimenters varied the width of the exits to allow just one mouse through, and then enlarged the opening to allow two mice, then three and so on. They also varied the distance between the exits. Second, each time one mouse escaped, they introduced another mouse into the pool to ensure the same level of panic among the mice. What did they find? The most efficient escape was when the door size was only large enough for one mouse to squeeze through. As the width of the door was increased, the mice stopped lining up and competed with each other. This actually slowed down the escape rate. This experiment suggests that an excess of resources increases competitiveness while a scarcity promotes co-operativeness.

There are examples even from nature to support this argument. According to experts, Australia has the least fertile soil on earth among all ecosystems. The soil contains about half the level of nitrates and phosphates found in similar and semi-arid regions elsewhere. The absence of glacial action or volcanic activity has meant that Australia's soils have not been replenished with nutrients for a long, long time. Plants in Australia have to work hard to get their nutrition and , having got it, need to protect it from grass and plant eating animals that live in the area. Inspite of these inhospitable conditions, however, there is an incredible diversity of plant life. It is host to some 12000 species of plants, a biodiversity that can rival a rainforest. There is a similar pattern for corals. For more than 2000km along the coastline of Australia, there stretches one of the world's largest collections of coral reef. Lack of physical protection makes these corals protect themselves and their location by producing some of the world's most potent toxins.

Eucalyptus trees in Australia develop large holes in their bases. A lay person would look upon this as a negative development on the assumption that this might weaken the tree base. In reality, the holes provide shelter for possums which leave nutrient-rich droppings as a sort of rent. So what is the explanation for this phenomenon of huge collaboration and cooperation?

In the Australian ecosystems, competition for resources is a rare phenomenon. Species tend to cooperate with each other to process, recycle and retain scarce nutrients. Scarce resources promote cooperation. Because resources are scarce, evolution selects only those species that cooperate to survive and grow. Nature favours those species that consume less, recycle efficiently and collaborate to keep the limited nutrient resources in circulation.

It is commonly believed that offering more choices and options to people adds to their happiness and sense of well-being. The reality is that, beyond a certain level of choice, the psychological impact of increasing choice is actually detrimental. A case that supports this is that, the Gross National Happiness of Bhutan decreased after different television channels were allowed to be broadcasted.

We can learn from these examples, from nature and others, that it is good to create a gap between the ambition and the resources. A feeling of fewer resources is a positive motivation. It stimulates positive action, as well as the collaborative instinct among people. The manager must try to create and maintain this gap between ambition and resources.

Before I sign off this blog I will leave with some of the well known examples of success this gap between ambition and resources has created:

- JFK's vision of putting a man on the moon had this gap.

- JVC developing the home video cassette recorder had this gap.

- US denying India access to supercomputing, helped India develop our own Param supercomputer.

Happy Reading

Ram

p.s The examples in this blog is taken from the book "The Bonsai Manager" by R GopalaKrishnan, again an excellent book to read.

1 comment:

A difference between nature and "organizations" is the existence of the feedback loop in nature. Nature for example will eliminate species that hod "resource". Not all organizations (or managers) do.

It is also my observation that "people" are a bit more dishonest (in their professions) than mice or plants are. That is to say that they hold opinions that are "distortions" of the reality. It is more common for people to see "scarcity" as an invitation to compete than to collaborate. A good manager should recognize such trends in the organization and act to bring about the necessary change in behaviour by suitabily altering the "rewards" (which is what nature does).

Real "scarcity" can promote "collaboration". If people just "feel" there is "scarcity", very little collaboration will result. I guess that is what the mice experiment proves. Managers will also need to make the "scarcity" real.

Post a Comment